Al Read

by Michael Patrick O'Leary

My parents took me on more than one occasion to see Al Read at the Gloucester ABC Regal some time in the 1950s. My father whispered to me confidentially that Al Read was not making any serious money from his performances because he had to pay nineteen shillings and sixpence in the pound as income tax. This was because he was a very rich man, a successful businessman, as well as being a comedian. My father told me that Al Read was wealthy as a result of his successful meat processing company. Read told Michael Parkinson that he came from a long line of sausages.

Alfred Read was born in Broughton, Salford in 1909. His trajectory into show business was an unusual one. Because of this, he gained strength to protect his originality and had the confidence and independence to resist the received wisdom of those seasoned professionials and impresarios who were expert at telling him how it had always been done. Read wanted to do something new and was not interested in repeating the tired old formulae. As he so wisely said: “amateurs built the Ark; professionals built the Titanic.”

Al soon found that he had a natural gift for the patter required to win new customers: ‘It was as if I was selling myself along with the brisket, tongue and boiled ham.’

He discovered his gift for identifying and isolating specific social types and when he returned home, he would practise imitating their accents and gestures. Early on, he spotted and developed one of the favourite characters of his later comedy routines – Johnny Knowall. He noticed many loudmouths on the terraces at Old Trafford when his father took him to watch Manchester United.

Some of his dry wit must have been inherited from his father. Some of the stories Al Read tells remind me of the wit and wisdom of my own father. As a child, Al overheard a friend of his father boasting about a pub in Liverpool where you could get ‘a pint of ale, a packet of Woodbines, a meat pie, and a woman and still have change out of a shilling’. Read’s father drew on his pipe and remarked, ‘couldn’t have been much meat in that pie.’

Al was called on to entertain his father’s friends by singing little songs like, ‘I’m a little brown mouse and I live in a house’. At North Manchester Preparatory Grammar School, he played Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. His real schooling in performance was when his father sent him out ‘on the van’ with a salesman called Bennett to sell Read Brothers meat products.

The family business prospered and Alfred became a director at the age of 23. Business gave him an outlet for performing. He was invited to attend the annual dinner dance of the Grocers’ Society and asked to provide some entertainment. He performed a version of Stanley Holloway’s ‘Albert and the Lion’ monologue and it went well enough to secure some new orders for cooked meats.

Joining the St Annes golf club was a good career move because he was able to befriend stars such as Sid Field when they were performing in Blackpool. Al suggested a couple of sketches to Field.

In 1940, he tried out his performing skills on the NAAFI’s northern buyer who lunched long and well every day at Liverpool’s Adelphi Hotel. Read was waiting for him one day when he got back to his office a little the worse for wear at 3 p.m. Read went through a routine using a custom-made gas mask case filled with samples. He secured a deal to supply the armed forces with two tons of luncheon sausage a week.

Read volunteered to join up but was in a reserved occupation so had to content himself with being a section leader in the Prestwich Home Guard. He also contributed to the war effort by devising an economical canned meal called Frax Fratters – fingers of meat in a potato casing. This was successful enough for comedians to work it into their acts.

Over the years, he became friendly with many people in show business. While entertaining some friends in a Blackpool bar with a prototype of the Loudmouth, Read was overheard by Peter Webster, who ran a children’s show on the pier. He offered him a spot in a weekly show at Midland Towers holiday camp. This led to an approach from impresario Jack Taylor, who offered him a spot in his show at the Regal Theatre on Blackpool’s South Pier.

He died a death but, soon after, Joe Hill offered him a spot at the Grand Theatre, Bolton as a replacement for Frank Randle, who had let them down. He did well enough to be taken on for a week but afterwards went back to the sausage factory, which he now ran because his father had retired.

In 1950, at the annual reception at the Queen’s Hotel, Manchester, which Al organised for the meat company’s big customers, he decided to entertain them with a routine featuring Johnny Knowall as a decorator. This went down well and the customers gathered around congratulating him. A man in a duffel coat detached him from the group and steered him towards the bar. He introduced himself as Barker Andrews, a producer with BBC Light Entertainment. Andrews said that he had overheard the performance of “The Decorator” and had decided on the spot that he must perform it on radio’s Variety Fanfare. Barker enthused: “You are going to change the potential of comedy, not only in this country but also the world”.

Read believed it was his great good fortune to be assigned Ronnie Taylor as his producer and he established an instant rapport with him. Taylor worked hard with Al –three days on a script for a ten-minute sketch – but managed to retain an air of spontaneity for the finished broadcast.

The BBC was delighted and pressed him to do more broadcasts. The problem was that Barker Andrews was thinking big. For a pilot show, other performers, including Patricia Hayes, and an orchestra were brought in. Al felt swamped and told Ronnie Taylor, “I don’t perform – I am.” The pilot was never broadcast and the BBC agreed to let him do it his way recording a monthly show, which would be broadcast in the prime Sunday lunchtime spot.

The introduction to his radio show was usually “Al Read: introducing us to ourselves”; and he himself described his work as “pictures of life”. He said that he never told gags and never tried to make people laugh. He drew on his own personal experience and observation of the small embarrassments and frustrations of daily life and encouraged the audience to be complicit with him by letting them draw their own conclusions by using the word “you”: “When you walk into a doctor’s surgery…”

Everything was achieved by suggestion and there was little need of props. Read had a pleasant speaking voice with an unobtrusive northern accent. He could switch from one character to another with a subtle change of tone. You knew when he was voicing a woman without him being exaggeratedly camp or effeminate. As he described it himself: “I was the listener and the talker, setting the scene with a few brushstrokes, some hand movements and the way I altered my stance, like a bulky woman shifting her weight from one bunioned foot to another and adjusting the delicate equilibrium of her generous bustline.”

Although he did not come to show business until his 40s, he then quickly became a star with three million listeners for each show without serving the usual apprenticeship. He was a national celebrity with his catch-phrases, “Right, monkey” and “You’ll be lucky” being repeated endlessly.

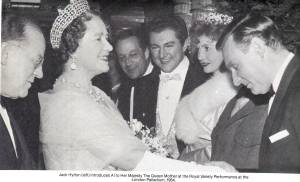

In 1950, he was asked to entertain the Royal Family and their household staff for a special Christmas concert at Windsor Castle. King George VI was particularly keen on Al’s gardening sketch and asked for a recording of it.

Al Read meeting two queens

Al was wary of television even though he realised he could not ignore it. In 1956, he decided to do some research in the USA and found a ready welcome in the English colony of Hollywood. James Mason introduced him to the gossip columnist Louella Parsons who gave him a mention but misnamed him “Hal Green”. He also met Noel Coward. He performed some of his sketches for Bob Newhart, who borrowed them and incorporated them into his own monologues.

He was invited to a party at which the singer Billy Daniels (“That Old Black Magic” – I also saw him at the ABC Regal, Gloucester) gave his wife a pink Cadillac wrapped in red ribbons. Al turned down the offer of a film role – it later became “The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw” starring Kenneth More and Jayne Mansfield.

George Burns advised him on TV technique: “Don’t fight the monster, Al. Make it work for you.”

Al was finally persuaded to take the plunge into television by Richard Armitage, a new kind of impresario- Cambridge-educated and a friend of David Frost, media mogul and conqueror of Richard Nixon. David Frost actually appeared in a touring summer show with Al and Jimmy Clitheroe. Al paints a bizarre picture of the future Sir David playing football on the beach at Weston-super-Mare with him and Jimmy Clitheroe (a comedian of restricted growth whom I saw on many occasions at Gloucester ABC Regal. Clitheroe made a career playing the character of an obnoxious and impudent schoolboy who never grew up- catch-phrase: ‘who knitted you, woolly ‘ead?!).

On stage or in the radio studio Al had felt a rapport with his audience. In the TV studio, he felt that the camera created a barrier. An article in Best of British described how Charles Chilton with “Journey into Space” managed to draw wonderful pictures in the radio audience’s mind with the most basic materials. Dylan Thomas created a world in sound with “Under Milk Wood” which was completely ruined on stage or on film. Al was canny enough to realise that his radio listeners built up their own images of his characters. He provided a framework and the audience became collaborators. Television is too literal. Al himself provided the sound of a dog for the radio show and ten different listeners would have described ten different kinds of dog. For television, a real dog had to be found and its paws had to be tied to a gate while it received instructions from an off-camera handler.

The BBC, in a characteristic fit of vandalism or penny-pinching (they must need to find ways of paying Jonathan Ross’s huge salary) wiped many of the tapes of Al’s radio shows as they did with TV shows of Tony Hancock and Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. The recordings that do survive demonstrate a rare talent.

Long before “alternative comedy” was thought of, he specialised in observational humour. To me his acute sense of the foibles of ordinary people’s behaviour and language make him a precursor of Mike Harding, Billy Connolly, Jasper Carrot, Richard Digance, Victoria Wood and Alan Bennett. Some of his monologues are positively Pinteresque.

The hilarious TV critic of the Guardian Weekly, Nancy Banks-Smith, is fond of quoting Al Read: “There was enough said at our Edie’s wedding.” This brilliantly and concisely conveys the kind of tight-lipped recognition of the resentment and bitterness that families try to suppress but often come out at social occasions, possibly fuelled by alcohol.

Despite the fact that most of his humor comes from observation of the foibles of the northern English working class, there was nothing flat-cap about him. He had always been wealthy, played golf and owned a yacht. He mixed easily with royalty, Hollywood stars and the upper crust. His second wife was a glamorous model.

Al should have had a career as a straight actor as did many other comedy greats like Jimmy Jewell, Stan Stennett, Charlie Drake and Dave King. I am privileged to have seen a brilliant performance in Hammersmith by Max Wall in Samuel Beckett’s “Krapp’s Last Tape”. According to the Internet Movie Database, Al played a DJ in one episode of “Casualty” broadcast posthumously in 1988.

He made a further radio series in 1976 and another in 1985 to coincide with the publication of his autobiography It’s All in the Book. Most of the information in this article is gleaned from that book, which was skilfully ghost-written by Robin Cross, who allows Al Read’s natural voice to come through. The book is out of print but copies are available from online booksellers such as Amazon or Abe Books. Also available are tapes and CDs of the remaining shows.

Al Read died on 9th September 1987 aged 78. His genius lives on through the surviving recordings, which are still regularly repeated on BBC radio more than 50 years after they were made.

Great piece! I was born in 1978 in Northern England and I can honestly say Read nailed my familys attitudes particularly my mother (born 1946)

since failing my driving test I actually find his driving instructor sketch so realistic that I can no longer listen without feeling physically unwell!

do you have any info on the Pianists Rabbich(sp?) & Landau who guested on the show, a google search didn’t bring up anything

thanks in advance

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Tim.

LikeLike

Great! New on me, another piece in the jigsaw of our comedy Four Bears.

LikeLike

Rawicz and Landauer if you’re trying to google them. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rawicz_and_Landauer

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Sheila. I remember them well.

LikeLike

[…] drafted this post before seeing a comprehensive piece on Padraig Colman’s blog, to which there’s little I can add except my admiration and the following […]

LikeLike

I found this while looking for information on Al Read for a short piece on my own blog https://thetrivialroundblog.wordpress.com/. You say just about all there is to say, particularly when there’s a shortage of relevant material on the web, so I have directed my readers here.

As it happens, I was a member of the British High Commission in Colombo from 1977 to 1981. I imagine it looks rather different now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Barrie. Your own blog looks very interesting and I will study bit further.

LikeLike

My Sinhalese father-in-law worked at the British High Commission in Colombo before taking the family to London in the 1970s. One of his colleagues was Anton Balasingham, later to find fame as the number 2 to Tamil Tiger leader Prabhakaran.

LikeLike

Interesting. What was your father-in-law’s name? I think I remember an Anton, but can’t be sure of the family name. Would he still have been there in 1981?

I had quite a lot to do with the press at the time and remember the two de Silva brothers. One was Mervyn, but I suppose they’ve long disappeared from the newspaper scene. Another de Silva (Rex?) was editor of The Sun.

LikeLike

My father-in-law’s name is Dukhinda Clarendon Jayawardena- known as ‘Duke’ or ‘Clarrie’. Mervyn de Silva has passed on. His son, Dayan Jaytallika, is also a writer and former ambassador. He is a good freind of mine and has supported my writing efforts. I pass on my old copies of Mojo magazine to him. I am not sure if Balasingham was at the high Commission in 1981. I will find out. His evil wife is still alive and living in New Malden.

LikeLike

Thank you. No, I don’t remember a Duke or Clarrie. If Anton is the one I’m thinking of, he worked in the information section, for which I was responsible. I never thought he had any political ambitions. We also had one Gordon Tyler, now deceased, I believe, and Desirée Barsenbach, subsequently married to William Woutersz, a Sri Lakan ambassador. Our librarian’s first name was Padmini. Don’t remember her second name.

LikeLike

Balasingham worked as a translator at the High Commission and left for the UK in 1971 when his first wife became seriously ill.

LikeLike

I forgot to mention that my MP (Conservative) is Ranil Jayawardena. I’d like to ask him if he‘s related to former President JR (or, indeed, your father-in-law), although I know it’s a common enough name.

LikeLike

JR used to send Christmas cards to my father-in-law but I think any family connection would be extremely tenuous. I have another friend who is an ambassador. He is a Tamil. He refers to JR in undiplomatic language as ‘that fucking bastard!’

LikeLike

Must be a different Anton, then.

JR seemed a venerable character, but the Tamil community will no doubt have seen him rather differently.

LikeLike

It looks as though Ranil Jayawardena is destined for advancement in the Truss government. He has been named as environment secretary. There is a piece in the issue of Private Eye dated 23 September 2022 reporting dodgy dealings he has with Serco. As he is a Tory of Sri Lankan heritage we should not be surprised if he is corrupt.

LikeLike

My friend, the Sri Lankan High Commissioner to Australia, New Zealand and Fiji, blames JR for the pogrom of 1983.

LikeLike

A friend of mine here in York owns the full collection of Al Reads scripts, annotated by Al himself. Priceless !

LikeLike

Wow! What a treasure trove! I would love to spend some time with that.

LikeLike

No chance he’d release the script about the dog, I suppose? I’d love to learn it in full as I’ve been doing a take-off of it for years.

LikeLiked by 1 person