Flann O’Brien and Catholicism Part 3

by Michael Patrick O'Leary

Here I continue dealing with the references to Catholicism in O’Brien’s work.

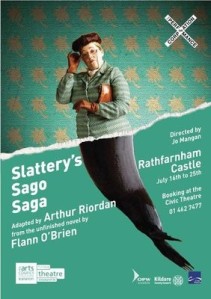

Slattery’s Sago Saga

In this short novella, Crawford MacPherson has a totalitarian philanthropic mission. She has seen the ill effects of Irish emigration on the United States:

“they bred and multiplied and infested the whole continent, saturating it with crime, drunkenness, illegal corn liquor, bank robbery, murder, prostitution, syphilis, mob rule, crooked politics and Roman Catholic Popery…Adultery, salacious dancing, blackmail, drug peddling, pimping, organising brothels, consorting with niggers and getting absolution for all their crimes from Roman Catholic priests…”

Her solution is to take over all Irish agricultural land and ban potatoes. The Irish dietary need for starch will be sated by sago.

The Hard Life

“Dedicated to Graham Greene, whose own forms of gloom I admire”.

This novel is set in the Dublin of 1890. Mr Collopy has become the guardian of his nephews, Finbarr (the narrator) and Manus. The boys attend prison-like schools run by the Christian Brothers in a regime of excessive corporal punishment. The Synge Street school attended by Finbarr was O’Brien’s own school.

Mr Collopy enjoys his drinking and talking sessions with the Jesuit, Father Fahrt, but is not averse to expressing strong opinions about the failings of the Catholic Church. “Oh the grand old Catholic church has always had great praise for sufferers… you won’t find Quakers or swaddlers coming out with any of this guff about suffering. They treat their employees right, they have proper accommodation for them, they know how to make plenty of money honestly and they are as holy – every man-jack of them – as any blooming Jesuit or the Pope of Rome himself”.

“A humble Jesuit would be like a dog without a tail or a woman without a knickers on her”. The Dominicans of the Spanish Inquisition were “blood-stained bowsies”. “The holy friars in Spain propagated the true faith by driving red hot nails into the backs of unfortunate Jewmen…Scalding their testicles with boiling water…And ramming barbed wire or something of the kind up where-you-know. And all AMDG [to the greater glory of God], to use your own motto, Father”. “If that’s the Catholic Church for you, is it any wonder there was a reformation? Three cheers for Martin Luther!”

Is Manus another version of de Selby who appears in footnotes in The Third Policeman and in person in The Dalkey Archive? He perverts science to quackery and exploits it for commercial gain.

Mr Collopy at times appears to be a proto-feminist. One of those human institutions about which to be pessimistic is the Dublin Metropolitan Corporation. Collopy is rallying the Dublin Corporation to provide public lavatories for women, and trying to persuade Father Fahrt to enlist the support of the church. They do eventually get an audience with the Pope, who becomes angry that Collopy is involving him in such a matter and in a mixture of Italian and Latin condemns him to hell.

According to Anthony Cronin, O’Brien was hopeful that the book would be banned. I have written elsewhere about how O’Brien was a post-modernist avant la lettre, even being an inspiration for the TV series Lost. As Keith Hopper has written: “One consequence of Irish censorship culture was that modernism almost passed Ireland by. By 1946, over 1,700 titles were proscribed on the grounds of ‘indecency’, including most of the leading international modernists. But if modernism was disallowed, postmodernism crept in through the back door, virtually unnoticed. At the start of the Second World War a trinity of Irish novels emerged which, in retrospect, mark the moment when high modernism began to drift, almost imperceptibly, into postmodernism: Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939), Beckett’s Murphy (1938), and Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds (1939). However, unlike Joyce or Beckett, Flann O’Brien never lived abroad. As a writer whose exile was interior, his textual strategies of silence, exile and punning are, by necessity, of a different order. In this respect, O’Brien’s particular brand of postmodernism must be read in two interrelated contexts: in an aesthetic domain (a challenge to the conceits of high modernism); and an ethical domain (a resistance to the nativist hegemony of Irish censorship culture).”

Being banned was a mark of distinction for an Irish author and O’Brien had not established himself. Often books were banned for alleged sexual obscenity (sex does not seem to have been O’Brien’s thing) but he gleefully expected that “the mere name of Father Kurt Fahrt SJ will justify the thunderclap”. He planned to challenge the ban in the high court and seek damages. He advised the publishers to make the book low-key in order to fool the “Reverend Spivs”. “Our bread and butter depends on being one jump ahead of the other crowd”.

There is an assumption in the book, says Cronin, “that the Catholic church is a very important institution, that it occupies a place of primary importance in the world, and that its existence affects life and one’s outlook on life in enormously important ways”.

The Pope’s angry reaction Mr Collopy’s campaign for a better lot for women makes the church seem, says Cronin, “ male, hierarchical and dismissive”. “A victory for Mr Collopy in the book’s terms would mean an acceptance of women as equal human beings and of their bodily needs as something of great importance. The Pope, supreme patriarch of a patriarchal world, draws back from such an acceptance. ‘Bona mulier fons gratiae’ he says. ‘Attamen ipsae in parvularum rerum suarum occupationibus verrentur. Nos de tantulis rebus consulere non decet’”. (A good woman is a fountain of grace. But it is themselves whom they should busy about their private little affairs. It is not seemly to consult us on such matters).

The Dalkey Archive

This book reworks material from the unpublished The Third Policeman and features De Selby and the constabulary’s atomic theory. The main character Mick Shaughnessy and his friend Hackett accidentally meet De Selby (philosopher, savant, mad scientist, quack?).

De Selby said: “I accepted as fact the story of the awesome encounter between God and the rebel Lucifer. But I was undecided for many years as to the outcome of that encounter. I had little to corroborate the revelation that God had triumphed and banished Lucifer to hell forever. For if- I repeat if – the decision had gone the other way and God had been vanquished, who but Lucifer would be certain to put about the other and opposite story?”

De Selby arranges an encounter with St Augustine in a cave under the sea. The Bishop of Hippo speaks with a Dublin accent and claims his father was Irish – “a proper gobshite”. He has little time for St Francis Xavier and St Ignatius Loyola. Xavier consorted with Buddhist monkeys and Loyola’s “saintliness was next to bedliness” and he led an army of “merchandisers”.

“Mick reminded himself that while he observed reasonably well the rules of the Church, he had never found himself much in rapport in the human scene with any priest. In the confessional he had often found their queries naïve , stupid, occasionally impertinent; and the feeling that they meant well and were doing their best was merely an additional exasperation. He was complete enough in himself, he thought: educated, tolerant, contemptuous of open vice or licentious language but ever careful to show charity to those who in weakness had strayed”.

When Mick meets James Joyce in Skerries, Joyce complains: “Even here, where my identity is quite unknown, I’m regarded as a humbug, a holy Mary Ann, just because I go to daily Mass. If there’s one thing scarce in Catholic Ireland, it is Christian charity”.

Mick decides he wants to give up the secular life and join the priesthood. “He said it with great sorrow, and God forgive him for saying it at all, but the great majority of Catholic curates he had met were ignorant men, possibly schooled in the mechanics of ordinary theology but quite unacquainted with the arts, not familiar with the great classical writers in Latin and Greek, immersed in a swamp of tastelessness. Still he supposed they could be discerned as the foot soldiers of the Christian army, not to be examined individually too minutely”.

Joyce himself wants to become a Jesuit: “I must be candid here, and careful. You might say that I have more than one good motive for wishing to become a Jesuit Father. I wish to reform, first the society, and then through the Society the church. Error has crept in…corrupt beliefs…certain shameless superstitions…rash presumptions which have no sanction within the word of the Scriptures…Straightforward attention to the word of God …will confound all Satanic quibble”.

Joyce dismisses the concept of the Holy Ghost and thereby the Holy Trinity: “The Holy Ghost was not officially invented until the Council of Constantinople in 381… The Father and Son were meticulously defined at the council of Nicaea, and the Holy Spirit hardly mentioned. Augustine was a severe burden on the early Church and Tertullian split it wide open. He insisted that the Holy Spirit was derived from the Father and the Son – quoque, you know. The Eastern Church would have nothing to do with such a doctrinal aberration. Schism!”

Cronin finds fault with The Dalkey Archive because the author “clearly expected his audience to gasp with shock before becoming overwhelmed with mirth at such schoolboy jokes as the questions de Selby puts to St Augustine in the cave and the saint’s answers”. “There is a clear impression that the author was trying to have it both ways, to affirm his orthodoxy while at the same time making an uneasy suggestion that a different view of things might be nearer the truth of existence as he sees it”.

Conclusion

O’Brien’s sense of his own Catholicism is defined to an extent by his relationship with Joyce. O’Brien asserts that Joyce “palliates the sense of doom that is the heritage of the Irish Catholic” with humour.

O’Brien’s contemporaries at UCD were divided between those who had a stake in an independent Ireland and those who did not. “Only the intellectuals felt uncomfortable, for it was they who were most irked by the Catholic triumphalism, the pious philistinism, the Puritan morality and the peasant or petit bourgeois outlook of the new state. But they were in an ambiguous position, though one which had its compensations, for in the first place they were themselves inheritors of whatever privileges were going, and in the second they found it almost impossible to break with formal Catholicism, either in belief or practice.

The hold of Catholicism in Ireland in those years was partly parental. To disavow the faith, whether in public or private, was a gesture so extreme that most people who had doubts or reservations suppressed them because it would cause their parents too much suffering, might even ‘break their hearts’. True, Joyce had managed the business a quarter of a century or so before, but the extreme song and dance he had made of it showed how difficult he found it; and he had, after all, to refuse to kneel at his mother’s bedside and to go into exile.

As Cronin puts it “self-interest, self deception, hypocrisy and fraud bulk large in all human affairs; and however much Myles na gCopaleen might devote himself to exposing them, his basic assumption is that they will continue to do so; nor does he ever show any gleam of admiration or enthusiasm for the countervailing modes of human behaviour, be they gallant, generous, visionary or, come to that, rational”.

Claude Cockburn, in his 1973 introduction to an edition of O’Brien’s Stories and Plays, referred to “two qualities of conditions which affect Irish writers not, by any means, exclusively, but with rare and particular intensity. Or you could call them two aspects of the same force. Fear of imminent hell or heaven, the sense of doom in the Irish Catholic heritage, can be seen as oppressive, constrictive”.

Cockburn suggests that the Catholic heritage was not necessarily restrictive for O’Brien. “Recognised and understood, the most rigid limitations can be transformed into productive conditions of achievement”. It is unfortunate that O’Brien’s achievements have been posthumous and that he did not transform these limitations into greater success or personal happiness in his lifetime. Nevertheless, O’Brien’s best writing is a cathartic expression of the fallen nature of humanity which bring pleasure for his readers.

[…] in the form of a Mylesian pub conversation). [1] Padraig Colman, in a fine series of detailed tributes, sums him up dispassionately as “a morose drunk who led an uneventful life as a senior civil […]

LikeLike